On Thursday nights, Mabel Hampton held court at the Lesbian Herstory Archives, opening the mail and gossiping with other archive workers. A devout collector of books on African-American history and lesbian culture, in 1976 Ms. Hampton had donated her lesbian paperback collection to the archives. Surrounded by these books and many others, she shared in welcoming the visitors, some of whom had come just to meet her.

Another more public place we could count on finding Ms. Hampton in her later years was New York's Gay Pride march. From the early 1980s on, Ms. Hampton could be seen strutting down Fifth Avenue, our avenue for the day, marching under the Lesbian Herstory Archives banner, wearing her jauntily tilted black beret, her dark glasses, and a bright red t-shirt proclaiming her membership in SAGE (Senior Action in a Gay Environment). Later in the decade, when she could no longer walk the whole way, a crowd of younger lesbian women fought for the privilege to push her wheelchair down the avenue.

Mabel Hampton, domestic worker, hospital matron, entertainer, had walked down many roads in her life--not always to cheering fans. Her persistent journey to full selfhood in a racist and capitalistic America is a story we are still learning to tell.

In recent years, I have been dazzled at our heady discussion of deconstruction, at our increasingly sophisticated academic conferences of gender representation, at the publication of sweeping communal and historical studies, and at our brave biographies of revered figures in American history in which the authors speak clearly about their subject's sexual identity. Mabel Hampton's is the story we are in danger of forgetting in our rush of language and queer theory.

Telling Mabel Hampton's history forces me to confront racism in my own relationship to her. Our two lives, Ms. Hampton's and mine, first intersected at a sadly traditional and suspect crossroads in the history of the relationships between black and white women in this country. These relationships are set in the mentality of a country that in the words of Professor Linda Meyers "could continue for over three hundred years to kidnap an estimated 50 million youths and young adults from Africa, transport them across the Atlantic with about half dying, unable to withstand the inhumanity of the passage."

In 1952, my short white Jewish mother took her breakfasts in a Bayside, Queens, luncheonette. sitting next to her was a short black Christian woman. For several weeks, they breakfasted together before they each went off to work, my mother to the office where she worked as a bookkeeper, Ms. Hampton to the homes she cleaned and the children she cared for.

One morning, Ms. Hampton told me, she followed my mother out to her bus to say good-bye and my mother, Regina, threw the keys to our apartment out the bus window, asking whether Ms. Hampton would consider working for her. "I told her I would give her a week's trial," Ms. Hampton said.

This working relationship was not to last long because of my mother's own financial instability, but the friendship between my mother and Ms. Hampton did. I remember Ms. Hampton caring for me when I was ill. I remember her tan raincoat with a lesbian paperback in its pocket, its jacket bent back so no one could see the two women in the shadows on its cover. I remember, when I was twelve years old, asking my mother as we did the laundry together one weekend whose men's underwear we were washing since no man lived in our apartment," They are Mabel's," she said.

In future years, Regina, Mabel and Mabel's wife, Lillian, became close friends, bound together by a struggle to survive and my mother's lesbian daughter. Much later, Ms. Hampton told me during one of her afternoons together that when Regina suspected I was a lesbian, she called her late one night and threatened to kill herself if I turned out that way. "I told her, she might as well go ahead and do it because it wasn't her business what her grown daughter did and besides I'm one and it suits me fine."

Because Ms. Hampton and I later formed an adult relationship based on our commitment to a lesbian community, I had a chance much later in life to reverse, when Ms. Hampton herself needed care, the image this society thrives on, that of black women caring for white people. The incredulous responses we both received in my Upper West Side apartment building when I was Ms. Hampton's caretaker in the 1980s showed how deeply the traditional racial script still resonated. To honor her, to touch her again, to be honest in the face of race, to refuse the blankness of physical death, to share the story of her own narrative of liberation--for all these reasons--it is she I must speak about tonight.

Ms.Hampton pointed the way her story should be told. Her legacy of documents so carefully assembled for Deborah Edel who had met Ms. Hampton in the early seventies and who had all of Ms. Hampton's trust, tell in no uncertain terms that her life revolved around two major themes--her material struggle to survive and her cultural struggle for beauty. Bread and roses, the worker's old anthem--this is what I want to remember, to share with you, the texture of the individual life of a working woman.

After her death on October 26, 1989, when Deborah and I were gathering her papers, we found a box carefully marked, "In case I pass away see that Joan and Deb get this at once, Mabel." On top of the pile of birth certificates and cemetery plot contracts was a piece of lined paper with the following typed entries:

1915-1919: 8B, Public School 32, Jersey City

1919-1923: Housework, Dr Kraus, Jersey City

1923-1927:Housework, Mrs. Parker, Jersey City

1927-1931: Housework, Mrs. Katim, Brooklyn

1932-1933: Housework, Dr. Garland, New York City

1934-1940: Daily Housework, different homes

1941-1944: Matron, Hammurland Manufactoring Co., NYC

1945- 1953: Housework, Mrs. Jean Nate

1948-1955: Attendant, New York Hospital

1954-1955:General, Daily Work

Lived 1935: 271 West 122nd Street

Lived 1939-1945: West 111th Street

Lived 1945-current (1955): 663 East 169th Street, Bronx, NYC

Compiled in the mid-fifties when Ms. Hampton was applying for a position at Jacobi Hospital, the list demanded attention--a list so bare and yet so eloquent of a life of work and home.

Since 1973, the start of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, I have felt Ms. Hampton's story must be told, but I am not a trained historian or sociologist. However, in the seventies, training workshops in doing oral histories with gay people were popping up around the city, and I attended every session I could. There, Jonathan Katz, Liz Kennedy, Madeline Davis and I would talk for hours, trying to come up with the questions that we thought would elicit the kind of history we wanted: What did you call yourself in the twenties? How did you and your friends dress in the forties? What bars did you go to? In the late seventies, when I started doing oral history tapes with Ms. Hampton, I quickly learned how limited our methods were.

"Joan: Do you remember anything about sports? Did you know women who liked to play softball? Were there any teams?

Mabel: No, all the women, they didn't care too much about them-- softballs--they liked the soft women. Didn't care about any old softballs. Cut it out!"

I soon realized that Ms. Hampton had her own narrative style, which was tightly connected to how she made sense of her life, but it wasn't until I had gone through every piece of paper she had bequeathed us that I had a deeper understanding of what her lesbian life had meant.

Lesbian and gay scholars argue over whether we can call a woman a lesbian who lived in a time when that word was not used. We have been every careful about analyzing how our social sexual representation was created by medical terminology and cultural terrors. But here was a different story. Ms. Hampton's lesbian history is embedded in the history of race and class in this country; she makes us extend our historical perspective until she is at its center. The focus then is not lesbian history but lesbians in history.

When asked "Ms. Hampton, when did you come out?" she loved to flaunt, "What do you mean? I was never in!" Her audiences always cheered this assertion of lesbian identity, but now I think Ms. Hampton was speaking of something more inclusive.

Driven to fend for herself as an orphan, as a black working woman, as a lesbian, Ms. Hampton always struggled to fully occupy her life, refusing to be cut off from the communal, national, and world events around her. She was never in, in any aspect of her life, if being "in" means withholding the fullest response possible from what life is demanding of you at the the moment.

Along her way, Ms. Hampton found and created communities for comfort and support, communities that engendered her fierce loyalty. Her street in the Bronx, 169th Street, was her street, and she walked it as "Miss Mabel," known to all and knowing all, whether it was the woman representing her congressional district or the numbers runner down the block. How she occupied this street, this moment in urban twentieth-century American history, is very similar to how she occupied her life--self-contained but always visible, carrying her own sense of how life should be lived but generous to those who were struggling to make a decent life out of indecent conditions.

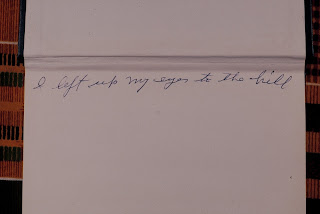

I cannot re-create the whole of Ms. Hampton's life, but I can follow her journey up to the 1950s by blending the documents she left, such as letters, newspaper clippings and programs with excerpts from her oral history and my interpretations and readings of other sources. These personal documents represent the heart of the Lesbian Herstory Archives; they are the fragile records of a tough woman who never took her eyes off the hilltop, who never let the tyranny of class keep her from finding the beauty she needed to live, who never accepted her traditional woman's destiny, and who never let hatred and fear of lesbians keep her from her gay community.

None of it was easy. From the beginning, Ms. Hampton had to run for her life.

Desperate to be considered for employment by the City of New York, Ms. Hampton began to document her own beginnings in April of 1963:

To the county clerk in the Hall of Records, Winston-Salem, North Carolina: Gentlemen: I would appreciate very much your helping me to secure my birth papers or any record you may have on file, as to my birth and proof of age as this information is vital for the purpose of my securing a civil service position in New York. Listed below are the information I have to help you locate any records you may have.

I was born approximately May 2, 1902 in Winston-Salem. My mother's name was Lulu Hampton or Simmons. I attended Teacher's College which is its name now at the age of six. My grandmother's name was Simmons. I lived there with her after the death of my mother when I was two months old. It is very important to me as it means a livelihood for me to secure any information."

On an affidavit of birth dated May 2, 1943, we find this additional information: Ms. Hampton was of the Negro race, her fahter's full name was Joseph Hampton (a fact she did not discover until she was almost twenty years old), and he had been born in Reidsville, North Carolina. Her mother's birthplace was listed as Lynchburg, Virginia.

This appeal for a record of her beginnings points us to where Ms. Hampton's history began: not in the streets of Greenwich Village where she will sing for pennies thrown from windows in 1910 at the age of eight, not even in Winston-Salem, where she will live on her grandmother's small farm from her birth until 1909, but further back into the past of a people, further back into the shame of a country.

Ms. Hampton's deepest history lies in the Middle Passage of the Triangular Slave Trade, and before that in the complex world of sixteenth- century Africa. When Europe turned its ambitious face to the curving coastline of the ancient continent and created an economic systems based on the servitude of Africans, Ms. Hampton's story began. The Middle Passage, the horrendous crossing of the waters from Africa to this side of the world, literally and figuratively became the time of generational loss. Millions died in those waters, carrying their histories with them. This tragic "riddle in the waters" as the Afro-Cuban poet Nicolas Guillen calls it, was continued on the land of the southern plantation system. Frederick Douglass writes in 1845, "I have no accurate knowledge of my age, never having seen any authentic record containing it." These words were written in 1845 and Ms. Hampton was born in 1902, but now as I reflect on Ms. Hampton's dedication to preserving her own documents, I read them as a moment in the history of an African-American lesbian.

The two themes of work and communal survival that run so strongly throughout Ms. Hampton's life are prefigured by the history of black working women in the sharecropping system, a history told in great moving detail by Jacqueline Jones in her study, Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow: Black Women, Work and Family from Slavery to the Present.Though Ms. Jones never mentions lesbian women, Ms. Hampton and her wife of forty-five years, Lilian Foster, who was born in Norfolk, Virginia, carried on in their lesbian lives traditions that had their roots in the post-slavery support systems created by southern black women at the turn of the century. The comradeship of these all-women benevolent and mutual aid societies was rediscovered by Ms. Hampton and Ms. Foster in their New York Chapters of the Eastern Star.

Even the work both women did, domestic service for Ms. Hampton and pressing for Ms. Foster, had its roots in this earlier period. Jones tells us that "in the largest southern cities from 50 to 70 percent of all black women were gainfully employed at least part of the year around the turn of the century." In Durham, North Carolina, close to Ms. Hampton's birthplace, during the period of 1880-1910, "one hundred percent of all black female household heads, aged 20 to 24, were wage earners." Very likely, both Ms. Hampton's grandmother and her mother were part of this workforce.

(Note: I am trying to capture on this new format the text and images I presented as my talk for the first David Kessler Award for Lifetime Achievement in NYC in 1992. Please be patient as I work out the technological challenges. I only wish I could share the music tape that Paula Grant created to accompany Ms. Hampton's life journey. All is done to honor this woman, who touched so many with her strength of spirit, her love of life, her generosities and social visions.)

No comments:

Post a Comment