The 1920s end with Mabel Hampton living fully 'in the life," trying to piece together another kind of living from her day work and from her chorus line jobs. Later, when asked why she left show business, she will say, "Because I like to eat."

The Depression does not play a large role in Ms. Hampton's memories, perhaps because she was already earning such a marginal income. We know that from 1925 until 1937, she did day work for the family of Charles Baubrick. Ms. Hampton carefully saved all letters from her employers testifying to her character.

December 12, 1937: "To Whom It May Concern: This is to certify that the bearer Mabel Hampton has worked for me for the last 12 years doing housework off and on and she does the same as yet. We have always found her honest and industrious."

Reading these letters, embedded as they were in all the other documents of Ms. Hampton's life, is always sobering. So much of her preserved materials testify to an autonomous home and social life, but these formal letters sprinkled through each decade remind us that in some sense Ms. Hampton's life was under surveillance by the white families who controlled her economic survival.

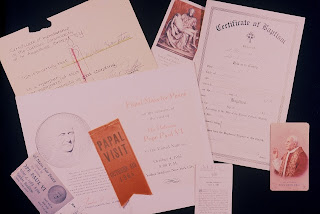

In 1935, Ms. Hampton is baptized into the Roman Catholic church at St. Thomas the Apostle on West 118th Street, another step in her quest for spiritual comfort. this journey would include a lifelong devotion to the mysteries of the Rosicrucian and a full collection of Marie Corelli, a Victorian novelist with a spiritualist bent. Ms. Hampton will end the decade registering with the United States Department of Labor trying to find a job. She is told, "We will get in touch with you as soon as there is a suitable opening."

The event that changes Ms. Hampton's life forever happens early on in the decade, in 1932. While waiting for a bus, she meets a woman even smaller then herself, "dressed like a duchess," as Ms. Hampton would later say. Her name was Lillian Foster and the two would remain together for the rest of Lillian's life. Ms. Foster remembers in 1976, two years before her death: "Forty-four years ago I met Mabel. We was a wonderful pair. I'll never forget it. But she's a little tough. I met her in 1932, September twenty-second. And we haven't been separated since in our whole life. Death will separate us. Other than that I don't want it to end."

Ms. Hampton, to the consternation of her more discrete friends, dressed in an obvious way much of her life. Her appearance, however, did not seem to bother her wife. Ms. Foster goes on to say;"A lady walked in once, Joe's wife, and she says, 'You is a pretty neat girl. you have a beautiful little home but where is your husband?' And just at that time, Mabel comes in the door with her key and I said, 'There is my husband.' Joe's wife said 'Now you know if that was your husband, you wouldn't have said it!' to which Ms. Foster firmly replied, "But I said it!"

Lillian Foster, born in 1906 in Norfolk, Virginia, shared much of the same Southern background Ms Hampton did, except she came from a large family. She was keenly aware that Ms. Hampton was "all alone" as she often put it. Ms. Foster worked her whole life as a presser in white-owned dry-cleaning establishments, a job, like domestic service, that had its roots in the neo-slavery working conditions of the urban South at the turn of the century. These many years of labor in poorly ventilated back rooms filled with chemical fumes accelerated Ms. Foster's rapid decline in her later years, but together with a group of friends, these two women would create a household that lasted for forty-six years, some of which were vary hard ones indeed.

This household with friends took many shapes. When crisis struck and a fire destroyed their apartment in 1976, as part of the real estate wars that were gutting and leveling the Bronx, Ms. Foster and Ms. Hampton came to live with me and Deborah Edel in our home, the home also of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, until they could move back into their own apartment. Later, Ms. Hampton would describe our shared time as an adventure in lesbian families. "Down here it was just like two couples, Joan and Deborah and Mabel and Lillian; we got along lovely, and we played, we sang, we ate; it was marvelous! I will never forget it. And Lillian, of course, Lillian was my wife. I had Joan laughing because I called Lillian, 'Little Bear,' but when I first met her in 1932, she was to me, she was a duchess--the grand duchess. Later in life, I got angry with her one day and I called her the 'little bear' and she called me 'the big bear' and of course that hung on to me all through life. And now we are known to all our friends as the 'big bear' and the 'little bear.'

In the Mabel Hampton--Lillian Foster collection at LHA, you will find dozens of cards signed "Big Bear," but when Ms. Hampton appealed to government officials or agencies for much needed help, as she often did as their housing conditions deteriorated, she spoke of Ms. Foster as her sister.

Letter to NYC Mayor Lindsay, 1969:

Dear Mr. Mayor, I don't know if I am on the right road or not, but I am taking a chance; now what I want to know is can you tell me how I can get an apartment, I have been everywhere and no success. I am living at the above address [639 E. 169th Street, Bronx] for 26 years but for about the past ten years the building has gone down terribly. For two years we have no heat all winter, also no hot water. We called the housing authority but it seems it don't help; everywhere I go the rent is so high that poor people can't pay it and I would like to find a place before the winter comes in with rent that I can afford to pay. It is two of us (women) past 65. I still work but my older sister is on retirement so we do need two bedrooms. If you can do something to help us it will be greatly appreciated.

Thanking you in advance,

I remain, Miss Mabel Hampton

There was no response from the Mayor's office.

Finding this letter marked a turning point in my work. Ms. Hampton's request for a safe and warm home for herself and her wife now stands at the starting point of all my historical inquiry: How did you survive?

In a document of a different sort, the program for a social event sponsored by Jacobi Hospital, where she was employed for the last twenty years of her working life, we discover that a Ms. Mabel Hampton and Ms. Lillian Hampton are sitting at Table 25. These two women negotiated the public world as "sisters," which allowed expressions of public affection and demanded a recognition of their intimacy.

There is a seamless quality to Ms. Hampton's life that does not fit our usual paradigm for doing lesbian history work. Her life does not seem to be organized around what we have come to see as the usual rites of gay passage, like coming out or going to the bars. Instead, she gives us the vision of an integrated life in which the major shaping events are the daily acts of work, friends, and social-political organizations and the major definers of these territories are class and race. In addition, she expects all aspects of her life to be respected.

Every letter preserved by Ms Hampton written by a friend, co-worker, or employer contains a greeting or a blessing for Ms. Foster. "I do hope to be able to visit you and Lillian some evening for a real chat and a supper by a superb cook! Do take care of yourself and my best to Lillian," from Dolores, 1944; "God bless and keep you and Lillian well always, I wish I could see you both some times," Jennie, 1977.

I really don't have words for the simplistic beauty of this history lesson - so I'll just put it in heart and leave it there as a reminder of whose shoulders I stand on

ReplyDelete